Whether piloting biplanes, fighter jets, or space craft, African Americans are integral to the history of flight. In celebration of Black History Month, let’s take a look at some of the black pioneers of aviation and aerospace.

Bessie Coleman (1892-1926)

- First African American woman to hold a pilot license

- First Native American woman to hold a pilot license

When Bessie Coleman tried to enroll in flight school, no school would accept her as a black woman. After discovering that she might have better luck overseas, Coleman began taking French lessons after work in the evenings, enabling her to complete French flight school applications. Once accepted, she trained in France and earned her pilot license from the Federation Aeronautique Internationale on June 15, 1921. Upon returning to the U.S., Coleman was a sensation, drawing large crowds to watch her aerobatic stunt flying. She used her popularity to fight discrimination by refusing to perform at events where crowds would be segregated. She also advocated for more African Americans and women to learn to fly, influencing many who would follow in her footsteps.

Cornelius Coffey (1902-1994)

- First African American to hold a pilot and aircraft mechanic license

- Founder of first African American-owned and certified flight school

Cornelius Coffey was already a skilled auto mechanic when he dreamed of becoming a pilot. Facing difficulty in applying to flight schools, he built his own plane and taught himself to fly it. In 1931, he organized a group of black flight enthusiasts and filed a lawsuit to be enrolled at Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical School, which had refused to admit him for being black. He also helped to start the Challengers Air Pilots’ Association in Chicago, including setting up an airfield in Robbins, Illinois. Coffey wanted to start a flight school open to anyone who wanted to learn to fly. He founded the Coffey School of Aeronautics and with the help of his wife, Willa Brown, his school facilitated the initial training for many of the Tuskegee Airmen.

Lieutenant Willa Brown (1906-1992)

- First African American woman to earn a pilot license in the U.S., as well as a commercial pilot license

- First African American woman officer in Illinois Civil Air Patrol

Inspired by her hero, Bessie Coleman, Willa Brown earned her pilot license in 1938 and her commercial pilot license in 1939. She married Cornelius Coffey and helped him run his flight school, training hundreds of pilots in the process. To bring attention to the school, Brown famously invited the editor of the Chicago Defender newspaper to an airshow. The editor personally attended and accepted her invitation to ride in her plane with her during the show. The exposure of this story led to even more popularity of the Coffey school and attention from the U.S. government, which eventually included the school in the Civilian Pilot Training Program. Brown’s efforts directly contributed to the eventual integration of America’s armed forces.

Guion ‘Guy’ Bluford (b. 1942)

- First African American to travel to space

A decorated Air Force pilot in the Vietnam War, Guy Bluford’s career led him to our very own Wright-Patterson Air Force Base as the staff development engineer and branch chief of the Air Force Flight Dynamics Laboratory. He decided to apply to NASA in 1978 and was accepted in 1979. Bluford’s first mission into space was August 30, 1983 aboard the Challenger. After the Challenger disaster in 1986, Bluford took some time away, earning a master’s degree in business administration. Finding that he was driven to continue his work at NASA, he returned to the program, completing additional space missions. He retired from NASA in 1993.

Tuskegee Airmen

- First Black military aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps (later U.S. Air Force)

With a shortage of trained white male pilots, the U.S. government lifted their ban on black pilots and began training African American men at the Tuskegee Army Airfield in Tuskegee, Alabama. 14,000 black men were trained as pilots, bombardiers, control tower operators, instructors, aircraft mechanics, and support staff. After completing 15,000 individual sorties in Europe and North Africa in World War II, the Tuskegee Airmen’s military units were among the most successful in the war, earning 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses and encouraging the integration of the armed forces in the process. Many of the Tuskegee Airmen would go on to careers in aviation and in the military, in what would eventually become the U.S. Air Force.

Dr. Mae C. Jemison (b. 1956)

- First African American woman astronaut

- First African American woman to travel to space

After completing a degree in chemical engineering at Stanford University, Jemison went on to earn a medical doctorate from Cornell University in 1981. She became a medical officer in the Peace Corps for Sierra Leone and Liberia where she taught as well as conducted medical research. In June 1987, she was accepted to NASA’s astronaut training program. On September 12, 1992, she became the first African American woman in space aboard the Endeavour. Jemison was the science mission specialist and conducted experiments on herself and the crew. She left the astronaut corps March 1993 and is currently a professor at Dartmouth College.

Stephanie Wilson (b. 1966)

- Most time logged in space for an African American astronaut

Stephanie Wilson earned a Bachelor of Science in engineering science at Harvard University in 1988, then went on to earn a Master of Science in aerospace engineering in 1992 from University of Texas at Austin. After applying to NASA, Wilson was selected as an astronaut in 1996. Her first space mission took place in 2006 and over the years and other missions, she has spent a total of 42 days in space, breaking previous records of time in space by the African American astronauts who came before her.

Eugene ‘Jacques’ Bullard (1895-1961)

- First African American combat aviator

After witnessing his father almost lynched, Bullard ran away from home in 1906, joining a band of nomadic performers. In 1912, he stowed away on a German merchant ship, landing in Aberdeen, Scotland. Bullard found a career in boxing, which gave him the opportunity to travel around Europe, eventually making it to Paris when World War I broke out. He joined the French Foreign Legion and fought bravely, with the French government awarding him the Croix de Guerre and Medaille Militaire. After joining the air service and training as a pilot, Bullard once again amassed a distinguished record (and was known to fly with his pet monkey on board). When the U.S. entered the war, he applied for a transfer to the U.S. armed forces. Not only was he denied the transfer, but the U.S. government also pressured France to ground him in order to uphold the U.S. policy against allowing African American pilots. France acquiesced, removing Bullard from aviation duty. Bullard’s service wasn’t yet over, however. He went on to open night clubs in Paris that ended up being popular with German officers in World War II. Being fluent in German made the officers trust Bullard with sensitive information, which he turned over to French counterintelligence. After moving back to the U.S., Bullard took on several odd jobs here and there. In 1959, the French government bestowed on Bullard the title of Chevalier in the Legion of Honor (similar to a knight in England).

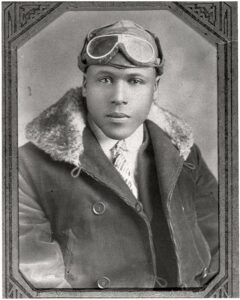

James Banning (1900-1932)

- First African American to fly coast-to-coast

With African American navigator Thomas Allen by his side, James Banning made history as the first black pilot to fly across the country. Motivated by a newspaper promising $1,000 to the first black pilot to make this coast-to-coast journey, Allen and Banning set out on September 19, 1932 in Los Angeles, California with only four spectators to see them off. This was intentional as Banning did not want to call attention to their trip in case they should crash in the attempt. The plane itself was barely airworthy with unreliable instruments and a compass that was perpetually off by around 30 degrees. While the plane technically operated with a 100-horsepower engine, Banning quipped, “I have reason to believe that some of the horses are dead.” With only $25 to their names, their flight plan was strategically designed to have them resting and refueling in areas where they were known so that they could lodge with friends of family, dine with in-laws, and benefit from donations along the way. Donations of any size were rewarded with the opportunity to sign the canvas wing of their biplane, which they called the “Gold Book.” News of their journey spread the closer they got to the finish line, and each city met them with larger and larger crowds. Allen and Banning made it to New York on October 9. Tragically, Banning died just four months later in an airshow accident but not before solidifying his place in aviation history.

Major Robert Lawrence (1935-1967)

- First African American astronaut

Earning a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry from Bradley University at the age of 20, Robert Lawrence wasted no time enjoying his early success and instead became an Air Force officer and pilot. In 1965, he earned his PhD in physical chemistry from Ohio State University. Lawrence completed the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School and was assigned to the Manned Orbital Laboratory Program (MOL) in 1967. Lawrence developed a maneuver called ‘flare’ that would go on to become an important part of space shuttle landing techniques. Unfortunately, Lawrence died in a crash during a training exercise later that year. With the secrecy around the MOL program, it would be years before Lawrence received the recognition he deserved for his contributions. To honor him, space shuttle Atlantis took his MOL mission patch into orbit in 1997 and presented it to his widow.